|

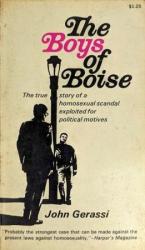

Written in 1965 about a same-sex sexual scandal that occurred in 1955 in Boise, Idaho (USA), John Gerassi's classic study depicts both middle America's traditional response to homosexuality and an era in the country's history before the modern gay rights movement really got underway. Because much of what Gerassi wrote about persists in today's struggles over gay and lesbian issues, his book still has much to tell us about how contemporary society reacts to, and misunderstands, homosexuality.” —Peter Boag On the morning of November 2, 1955, the people of Boise, Idaho, were stunned by a screaming headline in the Idaho Daily Statesman, THREE BOISE MEN ADMIT SEX CHARGES. Time magazine picked up the story, reporting that a “homosexual underworld” had long operated in Idaho's staid capital city. The Statesman led the hysteria that resulted in dozens of arrests—including some highly placed members of the community—and sentences ranging from probation to life imprisonment.

Quote: Glancing through Time magazine one day in December 1955, I was suddenly struck by a story headed “Idaho Underworld." Immediately I wondered what kind of underworld could possibly exist in such a sparsely populated, basically poor state, where no city was big enough for an oiganized crime syndicate to operate either extensively or profitably. But the first paragraph set me straight. It explained that there is a kind of underworld I had not imagined, or rather it referred to an underworld that I, born and bred in a big city, would never have characterized as an underworld at all:

Boise, Idaho (pop. 50,000), the state capital, is usually thought of as a boisterous, rollicking he-man's town, and home of the rugged Westerner. In the downtown saloons of the city a faint echo of Boise’s ripsnorting frontier days can still be heard, but its quiet residential areas and 70 churches give the city an appearance of immaculate respectability. Recently, Boiseans were shocked to learn that their city had sheltered a widespread homosexual underworld that involved some of Boise’s most prominent men and had preyed on hundreds of teen-age boys for the past decade.

My first impulse was not to believe it—unless, of course, the local police and law-enforcement agencies were part of that underworld, and had been all along. For how else, I asked myself, could such an underworld flourish for so long? In a city of 50,000 people, surely the cops must be aware of everything that goes on. And unless the ringleaders were so highly placed in the state’s political machinery that they were untouchable, someone certainly would have exposed their operations long before.

Even if the cops, the politicians, the judges, the newsmen and the big businessmen were part of this underworld—a very unlikely possibility—would not a group of outraged parents have banded together to clean up the mess? After all, kids are kids, and no matter how pleasant or profitable their extracurricular activities may be, they are bound to talk, to brag, or at least to betray themselves accidentally. What’s more, not all of these “hundreds of teen-age boys” could possibly have grown up to be confirmed homosexuals. Surely some, reaching adulthood during “the past decade” and having kids of their own, would have made an attempt to put a stop to it.

The article went on to say:

In the course of their investigation, police talked with 125 youths who had been involved. All were between the ages of 13 and 20. Usually, the motive—and the lure—was money. Many of the boys wanted money for maintenance of their automobiles (Idaho grants daylight driving permits to children of 14, regular licenses to 15-year-olds). The usual fees given to the boys were $5 to $10 per assignation.

Clearly, therefore, not all the “125 youths” were homosexual. Many simply catered to the adult homosexuals for money. But would not their parents have been suspicious of their children’s sudden independent wealth? Obviously, there was more to the story than Time reported.

Perhaps, I thought, Boise had become as liberal as New York, where homosexuals are rarely arrested (except in shakedowns), where young men and even teen-age boys freely drag the streets in makeup and wigs. After all, I reasoned innocently, Idaho had produced one of the most radical senators of the union—Glen Taylor, who had been on the Progressive Party ticket with Henry Wallace in 1948. But no, Boise was a small town, and no such American town could ever become so liberal as to allow homosexuals to wander about freely picking up thirteen-year-olds—for a whole decade!

Sure enough, the last paragraph of that Time story read:

This week the shocked community and the state began a rehabilitation program for the boys. Social workers began to investigate each case, to work out family problems. A citizens’ committee representing virtually every organization in Boise began a campaign to get afterschool jobs for the boys, and a special team of psychiatrists will arrive this week from Denver, at the expense of the State Board of Health, to treat the young victims.

But now my suspicions were aroused from a different angle. Where could Boise get the finances to carry out such a program of rehabilitation? If the community was really shocked, why had nothing been done for ten years? And where would Idaho find so many qualified social workers to handle the job?

Three weeks later, Time printed a short follow-up story on the Boise underworld. In two quick paragraphs, it reported that more homosexuals had been arrested—and sentenced. But it also said:

Dr. John L. Butler, chief of Idaho’s Department of Mental Health, had publicly opposed sentencing the homosexual adults to prison terms: "We have to build up community supports for them," he said. "One alternative might be to let them form their own society and be left alone."

This statement raised all sorts of new questions. For one thing, how did Idaho ever get such a progressive-minded mental-health chief, one who dared to propose measures even New York would consider outrageous? Secondly, what happened to the kids? Did not Dr. Butler's suggestion that the homosexuals should simply live together imply that they were all consenting adults?

Nor did the sentences make much sense. The range seemed to be from six months to life—in prison. What kind of a judge would send a homosexual to prison for life—prison being a notorious breeding ground for homosexuality anyway? There were other unanswered questions: How were the youths rehabilitated? If hundreds were involved, what happened to the schools? And what, in fact, did the community do about it, besides creating a few after-school jobs?

Two years later, I became an editor at Time magazine, and one of my first acts was to look up the Boise file in the morgue. But there was nothing more on the matter. No one had seemed interested in following it up. I decided that someday I would.

My preoccupation with international politics kept me pretty busy for the next few years, however, and instead of going to Boise, I went all over South America and wrote a book on the revolutionary upheavals gripping that continent But I never forgot the Boise story, and in 1965, ten full years after the scandal broke, I finally took the time to check it out. I went to Boise.

Before doing so, I read everything I could find on homosexuality and on child molesters. I interviewed many psychiatrists and psychologists who specialized in the subject, including some who had worked on the Kinsey reports. I also did as much research on Idaho, its history, customs, politics and resources, as was possible from the outside.

Once in Boise, I rapidly discovered that it was going to be harder to find the answers than I had thought. First of all, some of the court records had disappeared, while others had to be traced down to individual law offices. Also, very few people were willing to cooperate. The memory of the scandal was still fresh, and often sore. Many city and state officials wanted the scandal kept buried, not only because it reflected adversely on their city and their state, but also for personal reasons: Their own behavior during the scandal had been far from irreproachable. Finally, many of the principals no longer lived in Boise.

Nevertheless, as I persisted, I did get some breaks. I met a group of young lawyers and newsmen who began to help me. Although my investigation was bound to hurt the Republican Party, which was in power in 1955 and still ruled Boise in 1965, these people came from both sides of the political fence. Indeed, I obtained some very useful information from members of the Radical Right, despite the fact that they were (and, I presume, still are) stanchly opposed to all mental-health laws.

Some of these young men had been teen-agers during the scandal, and a few remembered particular details that gradually helped me fit together the over-all puzzle: why the scandal broke, how it was exploited and by whom, and what happened to the town as a result. Eventually I was able to track down many of the principals who had left Boise and were now living in Seattle, San Francisco, Florida and elsewhere. Dr. Butler, for example, did turn out to be the progressive-minded psychiatrist that the Time article had implied, but he had understandably fared poorly in Boise and was no longer there. I found him, as dedicated as ever, in Portland, Oregon.

With each new piece of evidence, my questions became more precise. But with each such question, I apparently became more of a threat. I began to receive anonymous phone calls warning me to drop my investigation. One day I got another anonymous phone call, but this time it was a friendly one. “Your motel is going to get ransacked,” the voice said. “You’d better hide whatever material you’ve accumulated.” I immediately put all my documentation into a suitcase, drove out to the airport, and sent it to New York. When I returned to my motel, sure enough, someone had gotten in and turned every drawer inside out.

Finally I heard that the governor himself, Robert E. Smylie, had written a letter to Newsweek's man in charge of the northwestern territory. I had made it perfectly clear that though I was (then) a Newsweek editor I was in Boise on my own time for a story or a book that did not involve Newsweek, and so I had violated no rules of conduct. But the very fact that he had written such a letter, or that it was so reported to me, made me apprehensive. I asked a friendly lawyer to make sure that he heard from me or contacted me at least once a day.

I stuck it out until I had documented the whole affair. When I did, I realized that the Time article had been misleading in many ways. I also concluded that the whole scandal was one of the most shocking examples of legalized prejudice, involving politics and personal vendettas, that I had ever come across. Homes were shattered, families were broken and individual careers were ruined, sometimes with incredible viciousness. And the fabric of a whole town was laid bare, revealing to what extent it rested on pettiness, intolerance and the personal ambition of a few.

I also understood, perhaps for the first time, what life in a small town is really like, and since America is ultimately made up of such small towns, I understood what America is really like. Because Boise is one of those typical American communities that has a single daily newspaper, I realized that the freedom of the press we cherish so much can be just as much of a farce in America as it is in countries where the press is controlled by the government. For what is the difference between a newspaper that prints only what the government tells it to and a newspaper that prints only what an all-powerful editor, catering to the establishment of the community, decides is news or fact?

Many of the men convicted for “infamous crimes against nature” in Boise in 1955 and 1956 should have been separated in some way from society: They were indeed child molesters. But the way the cases were handled not only illustrates the moral corruption of a small city wrought by its own stifling conformity and fears, it also exposes the quicksand on which so much of our American society is erected.

|